Informe acerca de gripe porcina (4. Mayo) - Hospital Zonal F

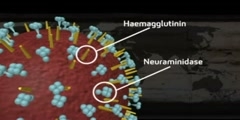

La Dra. Andrea Nieva integrante del Área de de Epidemiología del Hospital Zonal Francisco López Lima, brindó un informe acerca de la epidemia de gripe porcina./nGripe porcina/nLa gripe porcina es una enfermedad vírica que ataca a los porcinos pero ocasionalmente se transmite a los seres humanos. La gripe porcina (también conocida como influenza porcina o gripe del cerdo) es una enfermedad infecciosa causada por cualquier virus perteneciente a la familia Orthomyxoviridae, que es endémica en poblaciones porcinas. Estas cepas virales, conocidas como virus de la influenza porcina o SIV (por las siglas en inglés de «Swine Influenza Viruses») han sido clasificadas en Influenzavirus C o en alguno de los subtipos del género Influenzavirus A (siendo las cepas más conocidas H1N1, H3N2, H3N3 —aislada en Québec— y H1N2 —aislada en Japón y Europa). Aunque la gripe porcina no afecta con regularidad a la población humana, existen casos esporádicos de infecciones en personas. Generalmente, estos casos se presentan en quienes trabajan con aves de corral y con cerdos, especialmente los sujetos que se hallan expuestos intensamente a este tipo de animales, y tienen mayor riesgo de infección, de gripe porcina ,en caso de que éstos porten alguna cepa viral que también sea capaz de infectar a los humanos.Esto es debido a que los SIV pueden mutar y adicionalmente, mediante un proceso denominado reclasificación, adquirir características que permiten su transmisión entre personas. Además, tienen la capacidad de modificar su estructura para impedir que las defensas de un organismo tengan siempre la misma eficacia, ocasionando que los virus ataquen de nuevo con un mayor efecto nocivo para la salud. Es importante destacar que el brote de gripe H1N1 de 2009 en seres humanos y que se conoce popularmente como gripe porcina o influenza porcina, aparentemente no es provocado realmente por un virus de gripe porcina. Su causa es una nueva cepa de virus de gripe A H1N1que contiene material genético combinado de una cepa de virus de gripe humana, una cepa de virus de gripe aviaria, y dos cepas separadas de virus de gripe porcina. Los orígenes de esta nueva cepa son desconocidos y la Organización Mundial de Sanidad Animal (OIE) informa que esta cepa no ha sido aislada directamente de cerdos. Se transmite con mucha facilidad entre seres humanos, debido a una habilidad atribuida a una mutación aún por identificar,] y lo hace a través de la saliva, por vía aérea, por el contacto estrecho entre mucosas o mediante la transmisión mano-boca debido a manos contaminadas. Esta cepa causa, en la mayoría de los casos, sólo síntomas leves, y las personas infectadas se recuperan satisfactoriamente sin necesidad de atención médica o el uso de medicamentos antivirales./nClasificación/nGripe C Artículo principal: Influenzavirus C Es un virus perteneciente a la familia Orthomyxoviridae, que incluye a los virus causantes de la gripe. La única especie de este género se denomina «virus de la gripe C». Se ha confirmado que los virus de influenza C infectan a los seres humanos y a los cerdos, ocasionándoles gripe. Sin embargo, la gripe tipo C no es muy común en comparación con los virus de influenza A y los virus de influenza B, pero puede llegar a ser grave y ocasionar epidemias locales./nGripe A Artículo principal: Influenzavirus A Se sabe que la gripe porcina es ocasionada por los virus de la gripe A (H1N1), H1N2, H3N1, H3N2 y H2N3. En la población porcina existen tres subtipos del virus de la gripe A (H1N1, H3N2 y H1N2) que circulan en todo el mundo. En los Estados Unidos, el subtipo H1N1 había sido una causa frecuente de infección entre la población porcina hasta antes de 1998; sin embargo, desde finales de agosto de ese mismo año los subtipos H3N2 se aislaron en cerdos. A partir de 2004, las cepas virales H3N2 se aislaron en Turquía y Estados Unidos, aunque llegaron a encontrarse rastros genéticos de humanos (HA, NA y PB1), puercos (NS, NP, y M) y aves de corral (PB2 y PA)./nHistoria Hospital militar durante la pandemia de gripe española. El virus H1N1 es uno de los descendientes de la gripe española que causó una pandemia devastadora en la humanidad durante el periodo 1918–1919. Tras la finalización de la pandemia el virus persistió en cerdos, y con ello, los descendientes del virus de 1918 han circulado en seres humanos durante todo el transcurso del siglo XX, contribuyendo a la aparición normal de gripe estacional anualmente. Sin embargo, la transmisión directa de cerdos a humanos es bastante rara, pues sólo 12 casos se han demostrado en los Estados Unidos desde el 2005. El virus de la gripe ha sido considerado uno de los más esquivos conocidos hasta ahora por la ciencia médica, debido a sus transformaciones constantes para eludir los anticuerpos protectores que se han desarrollado tras exposiciones previas a gripes o vacunas. Cada dos o tres años, el virus sufre algunos cambios menores. Sin embargo, aproximadamente cada decenio, luego de que una gran parte de la población mundial ha logrado algún nivel de resistencia a estos cambios menores, el virus evoluciona drásticamente, lo que le permite infectar fácilmente a grandes grupos poblacionales a través del mundo y a menudo afectando a cientos de millones de personas cuyas defensas inmunológicas no están adecuadas para resistir su embate. El virus de la gripe también es conocido por realizar pequeñas variaciones de forma en periodos muy cortos de tiempo. Por ejemplo, durante la pandemia de gripe española, la oleada inicial de la enfermedad fue relativamente leve y controlada, mientras que la segunda oleada un año después fue altamente letal. A mediados de siglo, en 1957, una pandemia de gripe asiática infectó a más de 45 millones de personas en Norteamérica, ocasionando la muerte de 70.000 personas. En total causó casi 2 millones de muertes a nivel mundial. Once años más tarde, desde 1968 a 1969, la pandemia de gripe de Hong Kong afectó a más de 50 millones de personas causando unas 33.000 muertes y ocasionando unos $3.900 millones de dólares en gastos. En 1976, unos 500 soldados se infectaron con gripe porcina en un periodo de pocas semanas. Sin embargo, al final de ese mes, los investigadores encontraron que el virus había "desaparecido misteriosamente", literalmente. Durante el transcurso de un año promedio en un país como los Estados Unidos, hay aproximadamente unos 50 millones de casos de gripe "normal", que provocan la muerte de unas 36.000 personas. La mayoría de los pacientes afectados hacen parte de grupos en riesgo como personas extremadamente jóvenes o ancianas, enfermos y mujeres embarazadas, siendo un gran porcentaje de las muertes producto de complicaciones derivadas como neumonías. Investigadores médicos de todo el planeta han admitido que los virus de gripe porcina podrían mutar en algo tan letal como la gripe española y están vigilando cuidadosamente el último brote de gripe porcina de 2009 en aras de crear un plan de contingencia ante una posible e inminente pandemia global. Muchos países han tomado medidas de precaución y educación para reducir las posibilidades de que esto ocurra./nSignos y síntomas En porcinos Síntomas principales de la gripe porcina en cerdos. Los animales pasan por un cuadro respiratorio caracterizado por tos, estornudos, temperatura basal elevada, descargas nasales, letargia, dificultades respiratorias (frecuencia de respiración elevada además de respiración bucal) y apetito reducido. En algunos casos pueden producirse abortos en hembras grávidas. La excreción nasal del virus de la gripe porcina puede aparecer aproximadamente a las 24 horas de la infección. Las tasas de morbilidad son altas y pueden llegar al 100 por ciento, aunque la mortalidad es bastante baja y la mayor parte de los cerdos se recuperan tras unos 5 o 7 días tras la aparición de los síntomas de la gripe porcina. Sin embargo, la exacerbación de la enfermedad puede producir pérdida de peso y deficiencias en elcrecimiento, causando pérdidas económicas a los criadores, ya que los cerdos infectados pueden perder hasta 5.5 kilogramos de peso en un periodo de 3 a 4 semanas. La transmisión de la enfermedad se realiza por contacto a través de secreciones que contengan el virus (a través de la tos o el estornudo, así como por las descargas nasales)./nEn seres humanos Síntomas de la gripe porcina. La gripe porcina infecta a algunas personas cada año, y suele encontrarse en aquellos que han estado en contacto con cerdos de forma ocupacional, aunque también puede producirse transmisión persona a persona. Los síntomas en seres humanos incluyen: aumento de secreción nasal, tos, dolor de garganta, fiebre alta, malestar general, pérdida del apetito, dolor en las articulaciones, vómitos, diarrea y, en casos de mala evolución, desorientación, pérdida de la conciencia y, ocasionalmente, la muerte./nPatofisiología Véase también: Patogenia del virus influenza Los virus de influenza se enlazan mediante hemaglutinina en residuos de azúcares de ácido siálico en las superficies de las células epiteliales; típicamente en la nariz, garganta y pulmones de mamíferos o en el intestino de las aves. La gripe porcina en el cuerpo humano Las personas que trabajan con aves de corral y cerdos, en especial los que se exponen durante periodos prolongados, tienen un aumento en el riesgo de infección zoonótica con virus de gripe endémicos para estos animales, y constituyen una población de huéspedes humanos en los que eventualmente pudiera ocurrir una mutación por reordenamiento genético. La transmisión de gripe porcina a humanos con trabajos que tienen que ver con porcinos se documentó en un pequeño estudio de vigilancia realizado en el 2004 por la Universidad de Iowa. Éste y otros estudios forman la base de la recomendación para las personas con esta clase de trabajos (que involucren la manipulación de cerdos), quienes deberían ser objeto de mayor vigilancia epidemiológica. El brote de gripe H1N1 de 2009 fue causado por un reordenamiento de varias cepas de virus H1N1, incluidas una humana, una aviaria y dos porcinas./nInteracción con el virus H5N1 El virus de la gripe aviaria H3N2 es endémico para poblaciones de cerdos en China y se ha detectado también en Vietnam, aumentando las preocupaciones sobre la emergencia de nuevas cepas variantes. Se ha encontrado que los cerdos pueden ser portadores de virus de la gripe aviaria y de humanos, los cuales pueden combinarse (por ejemplo, intercambio de genoma homólogo mediante reordenación genética de subunidades) con el virusH5N1, haciendo un traspaso de genes y mutando en una nueva forma que podría transmitirse fácilmente entre humanos. En agosto de 2004, investigadores chinos hallaron la cepa H5N1 en cerdos. En el 2005 se descubrió que el H5N1 podría infectar hasta la mitad de la población porcina en algunas áreas de Indonesia, aunque sin causar sintomatología. Chairul Nidom, virólogo del centro de enfermedades tropicales en la Universidad Airlangga en Surabaya, Java Oriental, condujo una investigación independiente; se analizó la sangre de 10 cerdos aparentemente saludables y que se encontraban alojados cerca a granjas avícolas en Java Occidental donde la gripe aviaria había causado estragos. Cinco de las muestras contenían el virus H5N1. Diversos estudios clínicos realizados por el gobierno de Indonesia han encontrado resultados similares en la región. Pruebas adicionales hechas en 150 porcinos fuera de esa área mostraron ser negativos./nPrevención y tratamiento Ana Rivera, asesora de Salud Pública para los CDC, describe la influenza o gripe porcina: sus signos y síntomas, cómo se transmite, los medicamentos para su tratamiento, las medidas que las personas pueden tomar para protegerse de esta enfermedad y lo que deben hacer las personas si se enferman. Las medidas de prevención adecuadas contra las diversas formas de gripe en seres humanos son las que buscan evitar la transmisión —como el aislamiento, o el uso de mascarillas— y las vacunas, que preparan el sistema inmunitario para resistir la infección cuando ésta se produce. Las distintas cepas de la gripe, incluida la gripe estacional común, son suficientemente distintas como para que la vacuna contra una no sea efectiva contra otras; la vacuna para la gripe estacional no tiene ningún valor preventivo frente a la gripe porcina del 2009. Después de la crisis de gripe aviaria de 2005, los organismos internacionales y los sistemas sanitarios se prepararon para abordar el desarrollo y producción de vacunas específicas para afrontar sin demoras una posible pandemia. El uso de antibióticos, aunque puede ser apropiado a veces —sólo en caso de infección simultánea con bacterias y bajo indicación médica— no tiene ningún valor preventivo, y sí tiene, en cambio, los inconvenientes característicos del abuso de antibióticos: probable desarrollo de sensibilidad por el paciente, lo que anula la utilidad futura del tratamiento, y estímulo al desarrollo evolutivo de resistencia por las bacterias. El tratamiento sintomático es el propio de las gripes, basado principalmente en analgésicos. Sin embargo, hay que tener en cuenta que en niños y adolescentes se considera contraindicado el uso de aspirina (ácido acetilsalicílico) en caso de infección severa por los virus A o B de la gripe (el brote de gripe porcina de 2009 es de tipo A) o por el virus de la varicela, por el riesgo de que se produzca un cuadro poco común pero grave llamado síndrome de Reye; para los pacientes de menos de 19 años se recomienda, por ello, el uso de analgésicos alternativos. El tratamiento causal se basa en antivirales, sustancias que interfieren con la multiplicación del virus. Hay dos clases de antivirales inicialmente útiles contra la gripe, de las que una —la de los inhibidores de la enzima vírica llamada neuraminidasa— conserva la efectividad y la capacidad de evitar un desarrollo grave de la gripe cuando se necesita. Son dos las sustancias de esta clase, el oseltamivir (cuyo nombre comerial es Tamiflu), y el zanamivir (cuyo nombre comercial es Relenza). Después de la alarma producida en 2005 por la gripe aviaria, los gobiernos han acumulado las dosis consideradas necesarias para frenar una posible pandemia y evitar sus consecuencias. Vacunación contra la gripe porcina en cerdos Las estrategias de vacunación para el control y prevención del virus A/H1N1 en granjas porcinas incluyen típicamente el uso de muchas vacunas contra el virus bivalentes disponibles comercialmente en los Estados Unidos. De 97 cepas aisladas recientemente de H3N2, sólo 41 tenían fuertes reacciones serológicas cruzadas con antisuero a 3 de las vacunas comerciales contra SIV. Ya que la capacidad protectora de las vacunas de gripe dependen principalmente de la cercanía y similaridad entre el virus de la vacuna y el virus que causa la epidemia, la presencia de variantes no reactivas del virus H3N2 sugiere que las vacunas comerciales actuales podrían no proteger efectivamente a los cerdos de infecciones por una gran mayoría de virus H3N2./nEpidemiología: Brotes en porcinos Brote de 2007 en Filipinas El 20 de agosto de 2007 se investigó la aparición de gripe porcina en la región de Nueva Ecija y Luzon Central en Filipinas. Se encuentra una tasa de mortalidad menor al 10 por ciento para la gripe, si no había complicaciones como peste porcina. El 27 de julio de 2007, el departamento Nacional de Inspección de Carnes (National Meat Inspection Service o NMIS) de Filipinas, lanzó una alerta roja para peste porcina en Metro Manila y otras cinco regiones de Luzon luego de que se dispersara la enfermedad a granjas de cerdos en Bulacan y Pampanga, aun cuando se informó que las muestras de los animales eran negativas para el virus A/H1N1. Epidemiología: brotes en humanos Véase también: Gripe española La gripe porcina ha sido reportada como causante de zoonosis múltiples veces en seres humanos, siendo usualmente éstas de distribución bastante limitada. La pandemia de 1918 en seres humanos se asoció inicialmente con el H1N1, reflejando la posible zoonosis del patógeno, ya fuera del cerdo a humanos o viceversa. La evidencia disponible de ese tiempo no es suficiente para resolver tal interrogante, ya que se creía originalmente que la cepa evolucionó de una mezcla de virus de la gripe porcina (al que los humanos son más susceptibles) y de la gripe aviar, en donde las dos cepas se combinaron en un cerdo infectado por ambas al mismo tiempo. En análisis posteriores en muestras de tejidos recuperados de ese año revelaron que se trataba de la mutación de un virus de gripe aviaria y que posiblemente no hubo tal combinación con virus de gripe porcina. Dicha pandemia de gripe española infectó un tercio de la población mundial (o aproximadamente 500 millones de personas en ese tiempo), y causó alrededor de 50 millones de muertes./nBrote de 1976 en los Estados Unidos El 5 de febrero de 1976, un soldado recluta en Fort Dix manifestó sentirse agotado y débil. Murió al día siguiente y cuatro de sus compañeros tuvieron que ser hospitalizados. Dos semanas luego de su muerte, las autoridades de salud anunciaron que la causa de muerte fue un virus de gripe porcina, y que esa cepa específica parecía estar estrechamente relacionada con la cepa involucrada en la pandemia de gripe de 1918. El departamento de salud pública decidió tomar medidas para evitar otra pandemia de iguales proporciones, y se le notificó al presidente Gerald Ford que debía hacer que cada ciudadano de los Estados Unidos recibiera la vacuna contra la enfermedad. Aunque el programa de vacunación estuvo plagado de problemas de relaciones públicas y todo tipo de retrasos, logró vacunarse, hasta el momento de su cancelación, a un 24 por ciento de la población. Se estima en cerca de 500 casos la aparición de síndrome de Guillain-Barré, causados probablemente por una reacción inmunopatológica a la vacuna y de los cuales 25 terminaron en muerte por complicaciones pulmonares severas. Hasta la fecha, no se han encontrado otras vacunas de la gripe vinculadas al síndrome de Guillain-Barré. Brote de gripe porcina de 1988 En septiembre de 1988, un virus de gripe porcina mató a una mujer en Wisconsin, Estados Unidos, para posteriormente infectar a varios cientos de personas. Barbara Ann Wieners, mujer embarazada de 32 años, tenía 8 meses de gestación cuando ella y su esposo Ed se enfermaron tras visitar una granja de cerdos en la feria del condado de Walworth. Barbara murió ocho días después, aunque los médicos lograron inducirle parto y lograron salvar a su pequeña hija antes de morir. Su esposo se recuperó satisfactoriamente. Se reportaron numerosos casos de enfermedades similares a gripe en ferias porcinas, y se detectó que un 76 por ciento del grupo de expositores tenían niveles positivos de anticuerpos contra virus de gripe porcina, aunque no se detectaron cuadros clínicos de la enfermedad. Estudios adicionales sugieren que entre uno y tres trabajadores de la salud que tuvieron contacto con los pacientes desarrollaron enfermedad leve similar a la gripe con evidencia de anticuerpos contra virus de gripe porcina./nBrote de 2009 por H1N1 Metro de la Ciudad de México, 24 de abril de 2009: las personas con tapabocas tratan de protegerse de la epidemia de gripe porcina causada por una mutación de virus H1N1. Entre 2005 y 2007 el Centro para el Control de Enfermedades (Atlanta, Estados Unidos), reportó 5 casos de gripe porcina. El primer caso detectado en 2009 se detectó el 28 de marzo, según la conferencia de prensa ofrecida el 23 de abril del 2009 por la doctora Nancy Cox. Cronograma de el brote de Fiebre porcina de 2009, FoxNews (en inglés) En abril de 2009 se detectó un brote de gripe porcina en humanos, en México, que causó más de 20 muertes. El 24 de abril de 2009 el gobierno de la ciudad de México y el del Estado de México cerraron temporalmente —con el respaldo de la Secretaría de Educación Pública— las escuelas desde el nivel preescolar hasta el universitario, a fin de evitar que la enfermedad se extendiera a un área mayor. Hasta el momento se desconocen tanto el virus mutante que provocó la aparición de esta gripe porcina en los seres humanos, como la vacuna contra la misma. Hasta el 24 de abril de 2009 se conoce que existen casos confimados en humanos en los estados de San Luis Potosí, Hidalgo, Querétaro y Distrito Federal. En el municipio de Zumpahuacán del Estado de México se han reportado casos, algunos de los cuales han sido caso fatales. También se reportaron casos en Texas y en California, en los Estados Unidos. Según expertos, como el jefe del Departamento de microbiología del Hospital Mount Sinai de Toronto, el Doctor Donald Low, está por confirmarse la relación entre el virus de la gripe porcina H1N1 y el de los casos confirmados en México. Se ha recomendado a la población extremar precauciones de higiene: no saludar de beso ni de mano, evitar lugares concurridos (metro, auditorios, escuelas, iglesias, bancos, etc.), usar tapabocas y lavarse las manos constantemente con detergente o desinfectante como alcohol (alcohol en gel, por ejemplo) o hipoclorito de sodio (aunque este último está contraindicado, pues tiene efectos altamente tóxicos para la piel). En caso de presentar síntomas de gripe o temperatura elevada súbita, acudir a un hospital lo antes posible. En oficinas y cibercafés se recomienda limpiar teclados y ratones con alcohol para desinfectar y evitar una posible propagación del virus. El gobierno de la ciudad de México comenzó, el sábado 2 de marzo del 2009, a desinfectar a fondo las estaciones del Metro. La Secretaría de Salud (México) ha emitido una alerta por el brote en su sitio web. La Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México creó una página web especialmente para ofrecer información actualizada sobre el brote de gripe porcina. Se sabe que el virus causante de la gripe porcina no se transmite consumiendo carne de cerdo probablemente infectada, ya que el virus no resiste altas temperaturas como las empleadas para cocinar alimentos./nSOURCE: WIKIPEDIA/nSwine influenza - Swine influenza is endemic in pigs./nSwine influenza (also called swine flu, hog flu, and pig flu) refers to influenza caused by those strains of influenza virus, called swine influenza virus (SIV), that usually infect pigs. Swine influenza is common in pigs in the midwestern United States (and occasionally in other states), Mexico, Canada, South America, Europe (including the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Italy), Kenya, Mainland China, Taiwan, Japan and other parts of eastern Asia. Transmission of swine influenza virus from pigs to humans is not common and properly cooked pork poses no risk of infection. When transmitted, the virus does not always cause human influenza and often the only sign of infection is the presence of antibodies in the blood, detectable only by laboratory tests. When transmission results in influenza in a human, it is called zoonotic swine flu. People who work with pigs, especially people with intense exposures, are at risk of catching swine flu. However, only about fifty such transmissions have been recorded since the mid-20th Century, when identification of influenza subtypes became possible. Rarely, these strains of swine flu can pass from human to human. In humans, the symptoms of swine flu are similar to those of influenza and of influenza-like illness in general, namely chills, fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, weakness and general discomfort. The 2009 flu outbreak in humans, known as "swine flu", is due to a new strain of influenza A virus subtype H1N1 that contained genes most closely related to swine influenza. The origin of this new strain is unknown, however, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) reports that this strain has not been isolated in pigs. This strain can be transmitted from human to human, and causes the normal symptoms of influenza./nClassification Of the three genera of influenza viruses that cause human flu, two also cause influenza in pigs, with Influenzavirus. A being common in pigs and Influenzavirus C being rare. Influenzavirus B has not been reported in pigs. Within Influenzavirus A and Influenzavirus C, the strains found in pigs and humans are largely distinct, although due to reassortment there have been transfers of genes among strains crossing swine, avian, and human species boundaries./nInfluenza C Influenza C viruses infect both humans and pigs, but do not infect birds. Transmission between pigs and humans have occurred in the past. For example, influenza C caused a small outbreaks of a mild form of influenza amongst children in Japan, and California. Due to its limited host range and the lack of genetic diversity in influenza C, this form of influenza does not cause pandemics in humans./nInfluenza A Swine influenza is known to be caused by influenza A subtypes H1N1, H1N2, H3N1,H3N2, and H2N3. In pigs, three influenza A virus subtypes (H1N1, H3N2, and H1N2) are the most common strains worldwide. In the United States, the H1N1 subtype was exclusively prevalent among swine populations before 1998; however, since late August 1998, H3N2 subtypes have been isolated from pigs. As of 2004, H3N2 virus isolates in US swine and turkey stocks were triple reassortants, containing genes from human (HA, NA, and PB1), swine (NS, NP, and M), and avian (PB2 and PA) lineages./nHistory Swine influenza was first proposed to be a disease related to human influenza during the 1918 flu pandemic, when pigs became sick at the same time as humans. The first identification of an influenza virus as a cause of disease in pigs occurred about ten years later, in 1930. For the following 60 years, swine influenza strains were almost exclusively H1N1. Then, between 1997 and 2002, new strains of three different subtypes and five different genotypes emerged as causes of influenza among pigs in North America. In 1997-1998, H3N2 strains emerged. These strains, which include genes derived by reassortment from human, swine and avian viruses, have become a major cause of swine influenza in North America. Reassortment between H1N1 and H3N2 produced H1N2. In 1999 in Canada, a strain of H4N6 crossed the species barrier from birds to pigs, but was contained on a single farm. The H1N1 form of swine flu is one of the descendants of the strain that caused the 1918 flu pandemic. As well as persisting in pigs, the descendants of the 1918 virus have also circulated in humans through the 20th century, contributing to the normal seasonal epidemics of influenza. However, direct transmission from pigs to humans is rare, with only 12 cases in the U.S. since 2005. Nevertheless, the retention of influenza strains in pigs after these strains have disappeared from the human population might make pigs a reservoir where influenza viruses could persist, later emerging to reinfect humans once human immunity to these strains has waned. Swine flu has been reported numerous times as a zoonosis in humans, usually with limited distribution, rarely with a widespread distribution. Outbreaks in swine are common and cause significant economic losses in industry, primarily by causing stunting and extended time to market. For example, this disease costs the British meat industry about £65 million pounds every year./n1918 pandemic in humans The 1918 flu pandemic in humans was associated with H1N1 and influenza appearing in pigs, thus may reflect a zoonosis either from swine to humans, or from humans to swine. Although it is not certain in which direction the virus was transferred, some evidence suggests that, in this case, pigs caught the disease from humans. For instance, swine influenza was only noted as a new disease of pigs in 1918, after the first large outbreaks of influenza amongst people. Although a recent phylogenetic analysis of more recent strains of influenza in humans, birds, and swine suggests that the 1918 outbreak in humans followed a reassortment event within a mammal, the exact origin of the 1918 strain remains elusive./n1976 U.S. outbreak Main article: 1976 swine flu outbreak On February 5, 1976, in the United States an army recruit at Fort Dix said he felt tired and weak. He died the next day and four of his fellow soldiers were later hospitalized. Two weeks after his death, health officials announced that the cause of death was a new strain of swine flu. The strain, a variant of H1N1, is known as A/New Jersey/1976 (H1N1). It was detected only from January 19 to February 9 and did not spread beyond Fort Dix. This new strain appeared to be closely related to the strain involved in the 1918 flu pandemic. Moreover, the ensuing increased surveillance uncovered another strain in circulation in the U.S.: A/Victoria/75 (H3N2) spread simultaneously, also caused illness, and persisted until March. Alarmed public-health officials decided action must be taken to head off another major pandemic, and urged President Gerald Ford that every person in the U.S. be vaccinated for the disease. The vaccination program was plagued by delays and public relations problems. On October 1, 1976, the immunization program began and by October 11, approximately 40 million people, or about 24% of the population, had received swine flu immunizations. That same day, three senior citizens died soon after receiving their swine flu shots and there was a media outcry linking the deaths to the immunizations, despite the lack of positive proof. According to science writer Patrick Di Justo, however, by the time the truth was known — that the deaths were not proven to be related to the vaccine — it was too late. "The government had long feared mass panic about swine flu — now they feared mass panic about the swine flu vaccinations." This became a strong setback to the program. There were reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a paralyzing neuromuscular disorder, affecting some people who had received swine flu immunizations. This syndrome is a rare side-effect of modern influenza vaccines, with an incidence of about one case per million vaccinations. As a result, Di Justo writes that "the public refused to trust a government-operated health program that killed old people and crippled young people." In total, less than 33 percent of the population had been immunized by the end of 1976. The National Influenza Immunization Program was effectively halted on Dec. 16. Overall, about 500 cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), resulting in death from severe pulmonary complications for 25 people, which, according to Dr. P. Haber, were probably caused by an immunopathological reaction to the 1976 vaccine. Other influenza vaccines have not been linked to GBS, though caution is advised for certain individuals, particularly those with a history of GBS. Still, as observed by a participant in the immunization program, the vaccine killed more Americans than the disease did./n1988 zoonosis In September 1988, a swine flu virus killed one woman in Wisconsin, and infected at least hundreds of others. 32-year old Barbara Ann Wieners was eight months pregnant when she and her husband, Ed, became ill after visiting the hog barn at the Walworth County Fair. Barbara died eight days later, though doctors were able to induce labor and deliver a healthy daughter before she passed away. Her husband recovered from his symptoms. Influenza-like illnesses were reportedly widespread among the pigs at the farm they had visited, and 76% of the swine exhibitors there tested positive for antibody to SIV, but no serious illnesses were detected among this group. Additional studies suggested between one and three health care personnel who had contact with the patient developed mild influenza-like illnesses with antibody evidence of swine flu infection. However, there was no community outbreak./n1998 US outbreak in swine In 1998, swine flu was found in pigs in four U.S. states. Within a year, it had spread through pig populations across the United States. Scientists found that this virus had originated in pigs as a recombinant form of flu strains from birds and humans. This outbreak confirmed that pigs can serve as a crucible where novel influenza viruses emerge as a result of the reassortment of genes from different strains. 2007 Philippine outbreak in swine/nOn August 20, 2007 Department of Agriculture officers investigated the outbreak (epizootic) of swine flu in Nueva Ecija and Central Luzon, Philippines. The mortality rate is less than 10% for swine flu, unless there are complications like hog cholera. On July 27, 2007, the Philippine National Meat Inspection Service (NMIS) raised a hog cholera "red alert" warning over Metro Manila and 5 regions of Luzon after the disease spread to backyard pig farms in Bulacan and Pampanga, even if these tested negative for the swine flu virus./n2009 outbreak in humans Main article: 2009 swine flu outbreak The 2009 flu outbreak is due to a new strain of subtype H1N1 not previously reported in pigs. Following the outbreak, on May 2, 2009, it was reported in pigs at a farm in Alberta, Canada, with a link to the outbreak in Mexico. The pigs are suspected to have caught this new strain of virus from a farm worker who recently returned from Mexico, then showed symptoms of an influenza-like illness. These are probable cases, pending confirmation by laboratory testing. As of May 3, 2009, the new strain has not been reported in pigs in the UK. The new strain was initially described as apparent reassortment of at least four strains of influenza A virus subtype H1N1, including one strain endemic in humans, one endemic in birds, and two endemic in swine. Subsequent analysis suggested it was a reassortment of just two strains, both found in swine. Although initial reports identified the new strain as swine influenza (ie, a zoonosis originating in swine), its origin is unknown. Several countries took precautionary measures to reduce the chances for a global pandemic of the disease./nTransmission Electron microscope image of the reassorted H1N1 virus. The viruses are 80–120 nanometres in diameter. Transmission between pigs Influenza is quite common in pigs, with about half of breeding pigs having been exposed to the virus in the US. Antibodies to the virus are also common in pigs in other countries. The main route of transmission is through direct contact between infected and uninfected animals. These close contacts are particularly common during animal transport. The direct transfer of the virus probably occurs either by pigs touching noses, or through dried mucus. Airborne transmission through the aerosols produced by pigs coughing or sneezing are also an important means of infection. The virus usually spreads quickly through a herd, infecting all the pigs within just a few days. Transmission may also occur through wild animals, such as wild boar, which can spread the disease between farms./nTransmission to humans People who work with poultry and swine, especially people with intense exposures, are at increased risk of zoonotic infection with influenza virus endemic in these animals, and constitute a population of human hosts in which zoonosis and reassortment can co-occur. Transmission of influenza from swine to humans who work with swine was documented in a small surveillance study performed in 2004 at the University of Iowa. This study among others forms the basis of a recommendation that people whose jobs involve handling poultry and swine be the focus of increased public health surveillance. Transmission to humans usually does not result in influenza in humans.[50] When it does result in influenza, usually the influenza is mild[citation needed] and the basic reproduction number of the virus in human hosts is low enough that an outbreak does not occur. Interaction with avian H5N1 in pigs Pigs are unusual as they can be infected with influenza strains that usually infect three different species: pigs, birds and humans. This makes pigs a host where influenza viruses might exchange genes, producing new and dangerous strains. Avian influenza virus H3N2 is endemic in pigs in China and has been detected in pigs in Vietnam, increasing fears of the emergence of new variant strains.[52] H3N2 evolved from H2N2 by antigenic shift. In August 2004, researchers in China found H5N1 in pigs. These H5N1 infections may be quite common, in a survey of 10 apparently healthy pigs housed near poultry farms in West Java, where avian flu had broken out, five of the pig samples contained the H5N1 virus. The Indonesian government has since found similar results in the same region. Additional tests of 150 pigs outside the area were negative. Signs and symptoms/nIn swine In pigs influenza infection produces fever, lethargy, sneezing, coughing, difficulty breathing and decreased appetite. In some cases the infection can cause abortion. Although mortality is usually low (around 1-4%), the virus can produce weight loss and poor growth, causing economic loss to farmers. Infected pigs can lose up to 12 pounds of body weight over a 3 to 4 week period./nIn humans Main symptoms of swine flu in humans See also: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Symptoms of Swine Flu in YouTube Direct transmission of a swine flu virus from pigs to humans is occasionally possible (called zoonotic swine flu). In all, 50 cases are known to have occurred since the first report in medical literature in 1958, which have resulted in a total of six deaths. Of these six people, one was pregnant, one had leukemia, one had Hodgkin disease and two were known to be previously healthy. Despite these apparently low numbers of infections, the true rate of infection may be higher, since most cases only cause a very mild disease, and will probably never be reported or diagnosed. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in humans the symptoms of the 2009 "swine flu" H1N1 virus are similar to those of influenza and of influenza-like illness in general. Symptoms include fever, cough, sore throat, body aches, headache, chills and fatigue. The 2009 outbreak has shown an increased percentage of patients reporting diarrhea and vomiting. The 2009 H1N1 virus is not zoonotic swine flu, as it is not transmitted from pigs to humans, but from person to person. Because these symptoms are not specific to swine flu, a differential diagnosis of probable swine flu requires not only symptoms but also a high likelihood of swine flu due to the person's recent history. For example, during the 2009 swine flu outbreak in the United States, CDC advised physicians to "consider swine influenza infection in the differential diagnosis of patients with acute febrile respiratory illness who have either been in contact with persons with confirmed swine flu, or who were in one of the five U.S. states that have reported swine flu cases or in Mexico during the 7 days preceding their illness onset." A diagnosis of confirmed swine flu requires laboratory testing of a respiratory sample (a simple nose and throat swab)./nPrevention Prevention of swine influenza has three components: prevention in swine, prevention of transmission to humans, and prevention of its spread among humans. Prevention in swine Methods of preventing the spread of influenza among swine include facility management, herd management, and vaccination. Because much of the illness and death associated with swine flu involves secondary infection by other pathogens, control strategies that rely on vaccination may be insufficient. Control of swine influenza by vaccination has become more difficult in recent decades, as the evolution of the virus has resulted in inconsistent responses to traditional vaccines. Standard commercial swine flu vaccines are effective in controlling the infection when the virus strains match enough to have significant cross-protection, and custom (autogenous) vaccines made from the specific viruses isolated are created and used in the more difficult cases. Present vaccination strategies for SIV control and prevention in swine farms typically include the use of one of several bivalent SIV vaccines commercially available in the United States. Of the 97 recent H3N2 isolates examined, only 41 isolates had strong serologic cross-reactions with antiserum to three commercial SIV vaccines. Since the protective ability of influenza vaccines depends primarily on the closeness of the match between the vaccine virus and the epidemic virus, the presence of nonreactive H3N2 SIV variants suggests that current commercial vaccines might not effectively protect pigs from infection with a majority of H3N2 viruses. The United States Department of Agriculture researchers say that while pig vaccination keeps pigs from getting sick, it does not block infection or shedding of the virus. Facility management includes using disinfectants and ambient temperature to control virus in the environment. The virus is unlikely to survive outside living cells for more than two weeks, except in cold (but above freezing) conditions, and it is readily inactivated by disinfectants. Herd management includes not adding pigs carrying influenza to herds that have not been exposed to the virus. The virus survives in healthy carrier pigs for up to 3 months and can be recovered from them between outbreaks. Carrier pigs are usually responsible for the introduction of SIV into previously uninfected herds and countries, so new animals should be quarantined. After an outbreak, as immunity in exposed pigs wanes, new outbreaks of the same strain can occur./nPrevention in humans Prevention of pig to human transmission Swine can be infected by both avian and human influenza strains of influenza, and therefore are hosts where the antigenic shifts can occur that create new influenza strains. The transmission from swine to human is believed to occur mainly in swine farms where farmers are in close contact with live pigs. Although strains of swine influenza are usually not able to infect humans this may occasionally happen, so farmers and veterinarians are encouraged to use a face mask when dealing with infected animals. The use of vaccines on swine to prevent their infection is a major method of limiting swine to human transmission. Risk factors that may contribute to swine-to-human transmission include smoking and not wearing gloves when working with sick animals. Prevention of human to human transmission Influenza spreads between humans through coughing or sneezing and people touching something with the virus on it and then touching their own nose or mouth. Swine flu cannot be spread by pork products, since the virus is not transmitted through food. The swine flu in humans is most contagious during the first five days of the illness although some people, most commonly children, can remain contagious for up to ten days. Diagnosis can be made by sending a specimen, collected during the first five days for analysis. Recommendations to prevent spread of the virus among humans include using standard infection control against influenza. This includes frequent washing of hands with soap and water or with alcohol-based hand sanitizers, especially after being out in public. Although the current trivalent influenza vaccine is unlikely to provide protection against the new 2009 H1N1 strain, vaccines against the new strain are being developed and could be ready as early as June 2009. Experts agree that hand-washing can help prevent viral infections, including ordinary influenza and the swine flu virus. Influenza can spread in coughs or sneezes, but an increasing body of evidence shows small droplets containing the virus can linger on tabletops, telephones and other surfaces and be transferred via the fingers to the mouth, nose or eyes. Alcohol-based gel or foam hand sanitizers work well to destroy viruses and bacteria. Anyone with flu-like symptoms such as a sudden fever, cough or muscle aches should stay away from work or public transportation and should contact a doctor to be tested. Social distancing is another tactic. It means staying away from other people who might be infected and can include avoiding large gatherings, spreading out a little at work, or perhaps staying home and lying low if an infection is spreading in a community. Public health and other responsible authorities have action plans which may request or require social distancing actions depending on the severity of the outbreak./nTreatment In swine As swine influenza is rarely fatal to pigs, little treatment beyond rest and supportive care is required. Instead veterinary efforts are focused on preventing the spread of the virus throughout the farm, or to other farms. Vaccination and animal management techniques are most important in these efforts. Antibiotics are also used to treat this disease, which although they have no effect against the influenza virus, do help prevent bacterial pneumonia and other secondary infections in influenza-weakened herds./nIn humans If a person becomes sick with swine flu, antiviral drugs can make the illness milder and make the patient feel better faster. They may also prevent serious flu complications. For treatment, antiviral drugs work best if started soon after getting sick (within 2 days of symptoms). Beside antivirals, palliative care, at home or in hospital, focuses on controlling fevers and maintaining fluid balance. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of Tamiflu (oseltamivir) or Relenza (zanamivir) for the treatment and/or prevention of infection with swine influenza viruses, however, the majority of people infected with the virus make a full recovery without requiring medical attention or antiviral drugs. The virus isolates in the 2009 outbreak have been found resistant to amantadine and rimantadine. In the U.S., on April 27, 2009, the FDA issued Emergency Use Authorizations to make available Relenza and Tamiflu antiviral drugs to treat the swine influenza virus in cases for which they are currently unapproved. The agency issued these EUAs to allow treatment of patients younger than the current approval allows and to allow the widespread distribution of the drugs, including by non-licensed volunteers./nSOURCE: WIKIPEDIA

Channels: Medical

Tags: gripe porcina oms argentina rio negro general roca salud prevención vacunación recomendaciones Swine Flu

Uploaded by: cancer ( Send Message ) on 01-09-2009.

Duration: 2m 55s